Initially published in Global Gas Perspectives on 1 February 2018

The Naftogaz vs. Gazprom arbitration processes are a high-stakes game by any standard, and particularly so for Ukraine.

Michael Grossmann

- Overview of Stockholm arbitration process

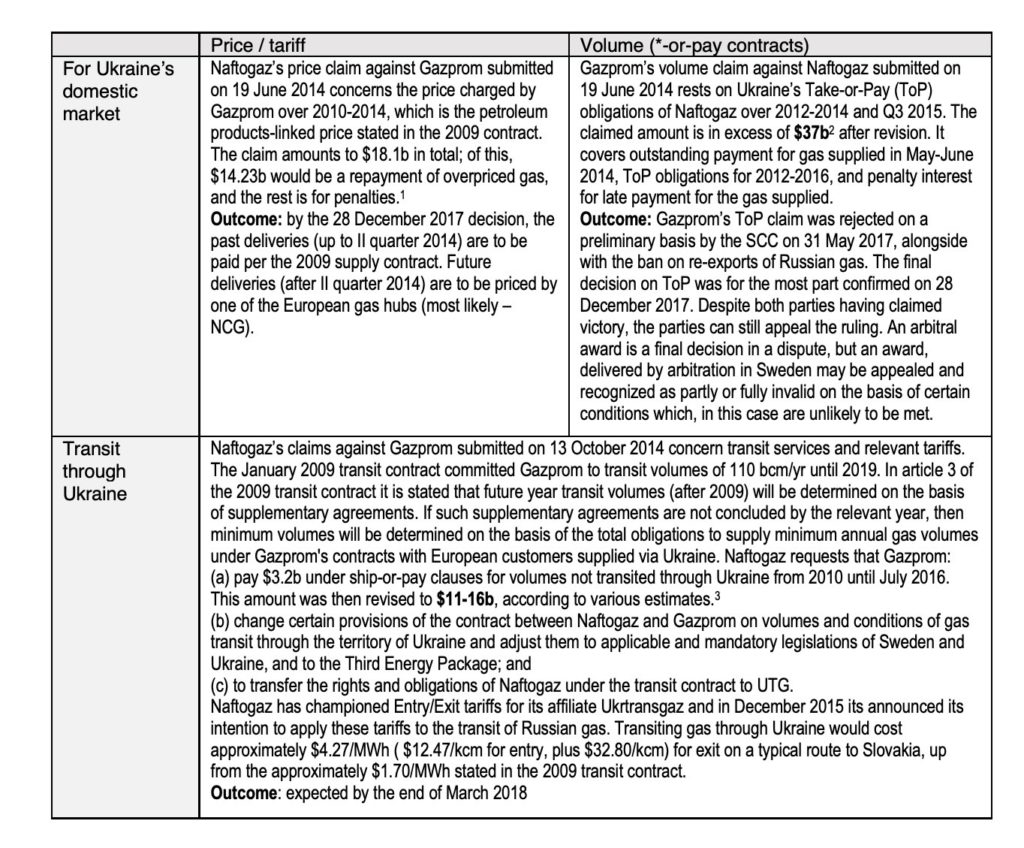

Traditionally, the price of Gazprom gas to Ukraine, and the tariff Ukraine charged for transit were linked de facto, so that changes in the price of gas from Russia to Ukraine were compensated by opposite changes in the transit tariff for Gazprom gas through Ukraine. There were other offsets as well, such as the leasing conditions for Russia’s naval base at Sevastopol, Crimea, or Ukraine’s suspending the signature of the EU-Ukraine association agreement. Since 2009, the linkage between price and transit was broken, with separate contracts being signed between Naftogaz of Ukraine and Gazprom regarding gas supply price and volume, and regarding transit volumes. The linkage between the two was also eroded with the commissioning of Nord Stream in 2011, which gave Gazprom the ability to deliver gas directly to Germany. The ruling of the Arbitration Institute of the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce (SCC) is not a public document, and therefore what is publicly known of it is what the contenders have announced about it. Below is a summary of the multi-billion gas supply case that has been ruled on, and the transit one that is still being examined at the SCC. All the cases relate to how the two contracts between Naftogaz and Gazprom are to be reinterpreted in light of a situation that has changed dramatically since the contracts were signed in January 2009: the crude oil market slumped from over $115/bbl to $45/bbl in the 6 months preceding the January 2009 contracts, and again from above $100/bbl to under $50/bbl in the 6 months following June 2014, when Naftogaz (presciently) lodged a complain against the price terms of the 2009 supply contract. On the political front, it may be argued that Ukraine’s territorial losses to Russia constitute an undeclared war, and thus a force majeureunder the terms of the 2009 contract, but to our knowledge, it has not been invoked.

On 13 October 2014 Naftogaz asked that rights and obligations of Naftogaz under the 2009 contract on volumes and terms of gas transportation through Ukraine in the years 2009-2019 be transferred to Ukrtransgaz. Such a transfer endorses the idea of separating Naftogaz’s transportation activities from its production and supply business. It makes Ukrainian energy law more compliant with European energy law. Naftogaz’s apparent hope is for EC-compliant Ukrainian law to govern the Contract, even though the escalation clause specifies Swedish law as the ultimate jurisdiction. There is irony in the fact that Naftogaz also explained to the government and to partners in reform that the high stakes of the arbitration process justify further postponing a long overdue unbundling of the gas transmission system.

- The price-and-volume awards

The 22 December 2017 ruling sets Naftogaz’s ToP obligations to Gazprom at 5 bcm (minus 1 bcm in ToP flexibility) per year until the end of 2019. This is far less than the 52 bcm/ yr amount stated in the 2009 supply contract and it is more in line with Ukraine’s now reduced import needs of about 16 bcm / yr. The 4-5 bcm / yr is also that much less gas that will reverse-flow into Ukraine from Europe. The direct Russian gas imports are to be priced at the German gas hub NCG. At time of writing, spot gas is priced at 17.85 € / MWh. Hub pricing is in the air of times in Europe and on the long term, this will contribute to integrating Ukraine’s gas market to Europe’s.

The court also handed down Naftogaz and Ukraine a political and economic victory when it confirmed that gas delivered to the territories under Russian occupation in the eastern Donbass did not constitute purchases by Naftogaz.

On the ToP claim, Naftogaz is to pay Gazprom $2.18b for gas not offtakenduring the ToP period. For comparison, Naftogaz earned about $2.46b in transit fees from Gazprom in 2016. A penalty of 0.03% of the ToP award is assessed for every day of delayed payment. Naftogaz announced it would settle this payment after the arbitration award on transit, expected at the time at the end of February 2018. The penalty would swell to $43m by that time. Following the December 2017 ruling, Fitch Rating affirmed Naftogaz’s long-term rating at CCC(‘Substantial credit risk’), while Gazprom’s stockprice remained stable.

Last but not least, the ruling on transit is to trigger the unbundling of the gas transmission system now operated by Ukrtransgaz. As mentioned, the arbitration process was the ostensible cause for postponing the unbundling of the gas transmission system. By executive resolution,[4]this process is to be initiated within 30 days of the final arbitration ruling. Curiously, there are two competing concepts for the unbundling: Naftogaz’s concept is to emulate the way Poland’s PGNiG spun off Gaz-System in 2004-2005. For that it retained PwC Poland as its advisor in June 2017; in August 2017 it appointed a Gaz-System director technical director as president of the country’s TSO; and in October 2017 it retained the investment bank Rothschild S.p.A. (Milan) to assist in the search for an operating partner TSO for its TSO affiliate. Considering the threats to Ukraine’s gas “transit industry”, there is a consensus that the Ukrainian operator could benefit from having a TSO operating partner who would be politically acceptable to Ukraine, to Gazprom, and to the trading counterparts of both. In December 2017, Ukraine’s Ministry of Energy and Coal Industry initiated its own search for partners, addressing directly EU-based and US TSOs to submit by 1 February 2018 expressions of interest in partnering with the Ukrtransgaz successor firm, Main Gas pipelines of Ukraine (MGU). By Cabinet of Minister’s resolution, MGU is to operate the assets that are on Ukrtransgaz’ balance. Since then, Naftogaz has withdrawn from the process of searching for a TSO partner.[5]The main stumbling block for investors’ or partners’ investment in Ukraine’s gas transmission system lies in these assets definition as “strategic” and therefore non-privatizable in any shape or form. A Concession Law framework is being overhauled, but is still a long way from being enacted into law. On the short term, another legal vehicle will be needed for the TSO partner to invest in, and benefit from its involvement in gas transmission or transit in Ukraine.

- The consequences of the ruling beyond Ukraine

The preliminary 29 May 2017 ruling on re-exports of gas was in line with similar EU rulings where the European Commission attacked Gazprom for its discriminatory pricing practices and destination clauses in its supply contracts. It opens the possibility for traders currently supplying the Ukrainian market to re-export their excess volumes further West, or even to purchase at the Russian-Ukrainian border. The attractiveness of the Ukrainian route will depend on its tariff offering (Naftogaz has proposed to lower considerably its transit fees after 2019), but also on the existence of physical alternatives routes to Ukraine to supply Southeastern Europe. Even if a second pair of additional Nord Stream lines were to be built and came online at thestart of 2020, and absent a Turkstream line to Europe, much gas would still need to transit through Ukraine.EWI Scenarios & Research ran its TIGER model[6]to simulate economic gas flows with prices of gas and LNG and exiting tariffs as inputs, and pipeline and terminal capacities. The model runs do not show the additional offshore pipelines to have a material effect on flows on the benchmark Ukraine to Slovakia flow, with approximately 21.5 bcm / yr with and without NS2. Other lesser transit flows to Hungary and Romania/Moldova are equally unaffected, at 3.4 bcm / yr and 5.4 respectively.[7]

To put the arbitration process in perspective, arbitral awards are not court decisions and therefore they do not constitute precedents for other cases being examined in European courts. This case, together with the ongoing complaint of the Russian Federation against the EU under the WTO’s GATT address the question of whether EU energy law can be applied to contracts involving at least one non-EU entity. According to Ana Stanic, founder of E&A Law, in the WTO case, the Russian Federation is inter alia challenging Article 11 of the Third Energy Package Gas Directive (known as the Gazprom clause) which sets out different rules for certification of TSOs owned by non-EU entities to EU-owned ones as breaching GATT and its provisions. The WTO’s decision is expected in June-July 2018.

The ToP decision does make direct sales of Russian gas to Ukraine likely again. The lifting of the re-export ban means Ukraine-based traders could purchase gas for domestic market needs, and adjust marginal amounts by re-exporting. It also means that starting in 2020, MGU could in theory become a transit operator in its own right.Whether this will actually happen depends on

(1) the competitiveness of the tariff proposal of MGU. The Ukrtransgaz tariffs currently in place are generally recognized as high by regional standards. Ukrainian transit costs approximately 3.43€/MWh ($45.27/thousand m3: $12.47/thousand m3for entry, plus $32.80/thousand m3for exit). This is to be compared with the 2009 contractual transit tariff of about $1.70/MWh ($1.70 / thousand m3/ 100 km), but also with an estimated 2.62 €/MWh[8]for the direct Russia-to-Germany route over the existing Nord Stream line. If the transit tariffs remain at their current levels, they will not contribute to the attractiveness of Ukraine as a transit country, and they will undermine Naftogaz’s economic argument against Nord Stream 2;

(2) the reliability of Ukraine’s TSO. This is not so much a technical issue: though Ukraine’s transit capacity has declined since its peak in the early nineties, it is still far superior to the transit volumes envisioned from 2020 onwards. It is mainly a commercial issue: changes in tariffs must be announced at least one gas year in advance of taking effect, and under normal operating conditions they should only happen during regulatory tariff review periods;

(3) the willingness of Gazprom to sell at the Russian-Ukrainian border. Gazprom, as the region’s dominant supplier, remains best placed to capitalize on the optionality that Ukraine can offer, thanks to its common borders with five east European gas markets, and thanks to its abundant storage capacity. This optionality is an advantage that Gazprom would probably not give away to would-be buyers at the Russian-Ukrainian border.

Though the Russian-Ukrainian gas war remain fraught with geopolitics, the arbitration processes will probably revert these countries’ commercial gas relations to the status quo ante bellum, albeit with a transparent and market-based mechanism.

[1]Nafogaz 3Q 2017 unaudited account p33

[2]IFRS consolidated Interim condensed financial information (unaudited) 30 September 2017

[3]2016 Gazprom Financial Report, p77

[4]Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine Resolution №496 or 1 July 2016

[5]https://www.epravda.com.ua/rus/news/2018/01/24/633338/

[6]Impacts of Nord Stream 2 on the EU Natural Gas Market, EWI Energy Research & Scenarios, September 2017

[7]The simulation does not allow direct supplies from Russia to Ukraine, in line with Naftogaz’s decision not to import gas from Russia.A criticism of the simulation can be made that it constrains transit through Ukraine at 30 bcm/yr which, seen from today, seems excessively pessimistic in view of current transit volumes. A new simulation relaxing this constraint is expected to be run in February 2018.

[8]see Mikhail Korchemkin’s estimate of the Nordstream implied tariff at https://eegas.com/ns-cost-volume-2014-2016e.htm